In Frank Herbert’s seminal science fiction epic Dune, the backdrop of galactic politics, mysticism, and ecological struggle is haunted by the shadow of an ancient war: the Butlerian Jihad. Thousands of years before the events of the novel, humanity waged a ferocious battle against intelligent machines—sentient computers and AI systems that had, in Herbert’s vision, come to dominate and dehumanize their creators. The aftermath of this cataclysmic conflict was a galaxy-wide ban on any form of artificial intelligence, enshrined in law and religion: “Thou shalt not make a machine in the likeness of a human mind.”

In place of AI, human capabilities were honed and elevated. The Mentats became living computers, trained to calculate and strategize with machine-like precision. The Bene Gesserit order trained their minds and bodies to extremes of perception and control. And the Spacing Guild, using the spice melange, birthed Navigators who could fold space without the aid of computation.

But this rejection of machines was not merely technological—it was philosophical. The Butlerian Jihad represented a revolt against dependence, a reclaiming of human dignity in the face of its outsourcing to algorithms.

Echoes in Our Present

Today, we stand at the cusp of a real-world transformation. The rise of large language models like GPT-4, image generators, autonomous drones, and decision-making algorithms in finance, law, and warfare brings us uncomfortably close to Herbert’s forbidden frontier.

We are not (yet) ruled by AI overlords, but many of our systems—economic, social, and political—are increasingly influenced by AI decision-making. From predictive policing to hiring algorithms to autonomous weapons, we face a growing question: Are we building tools, or are we constructing new masters?

This moment is not science fiction. The most prominent voices in AI today, from Elon Musk and Sam Altman to Geoffrey Hinton and Stuart Russell, echo concerns that Herbert might recognize. They ask whether alignment is possible, whether intelligence—once unleashed—can be contained, and whether human values can survive recursive self-improvement cycles of machine learning.

The Modern Jihad?

No revolt has yet begun. There is no Butlerian Jihad on our horizon—at least not in the form of armed rebellion. But a philosophical and regulatory pushback is gaining ground. Governments are debating AI oversight. AI ethicists warn of algorithmic bias, explainability gaps, and the moral hazards of autonomous weapons. The Vatican, the European Union, and Silicon Valley start-ups alike are asking versions of the same question: How far is too far?

What differs from Herbert’s universe is the ambiguity of agency. In Dune, machines became oppressors. In our world, AI reflects our own incentives and blind spots. If our systems are racist, biased, or unjust, it is because we built them that way—or failed to prevent it.

Samuel Butler: The Man Behind the Myth

The term Butlerian Jihad pays homage to Samuel Butler, a 19th-century writer and early critic of unexamined technological progress. In his 1863 essay Darwin Among the Machines, published in The Press, Butler speculated that machines might evolve through natural selection to surpass humanity. He envisioned a future where machines could become self-replicating and intelligent, ultimately rendering humans obsolete. His warning was not against machines per se, but against blind faith in them.

Butler’s essay inspired later science fiction, including Herbert’s use of his name to symbolize a historical revolt. It remains one of the earliest philosophical critiques of AI, long before computers were even imagined.

Conclusion: A Choice Before the Jihad

We may not need a jihad. Unlike Herbert’s distant future, we still have the ability to shape how our technologies are built, deployed, and governed. The question is not whether AI is dangerous—it is whether we are wise enough to design systems that enhance rather than erode human autonomy.

If we fail, the future may look less like Dune and more like its prelude. But if we succeed, perhaps we can realize a synthesis that Herbert’s world could not imagine: a partnership between intelligence—human and artificial—that preserves what is most vital in us.

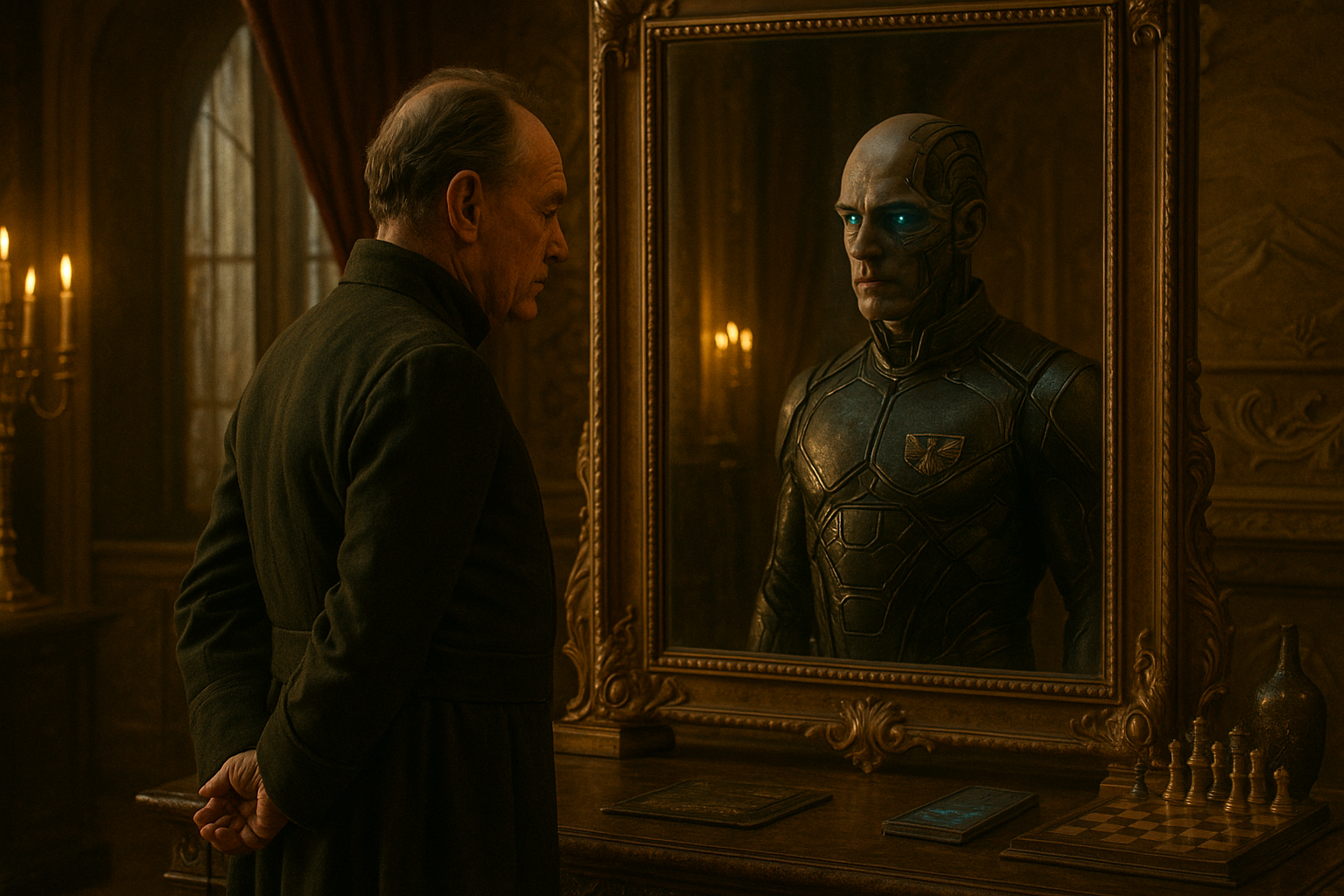

In the end, Dune is not just a warning. It is a mirror. And the reflection it shows us depends on what we choose to become.