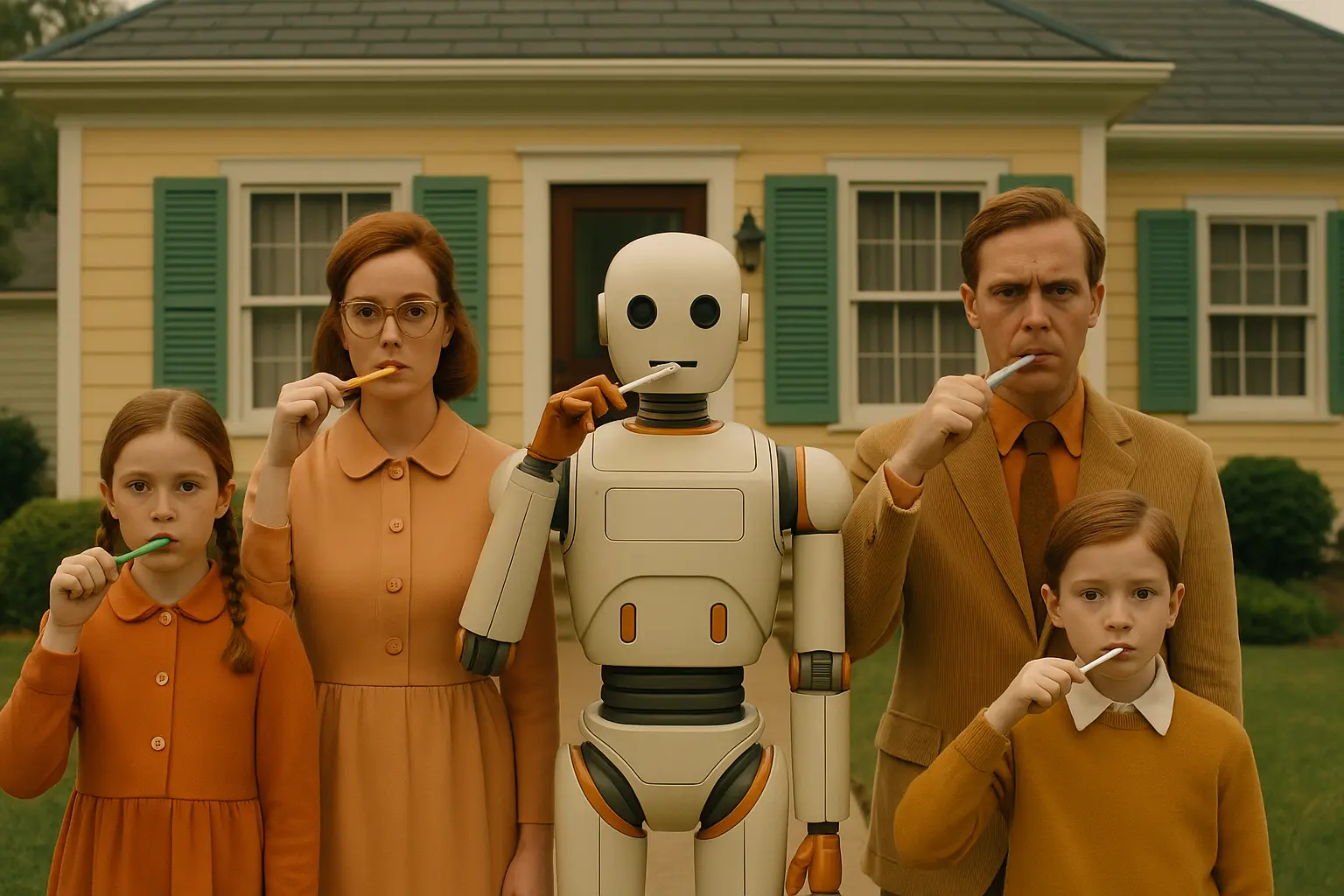

Brushing Up on Saturation

Imagine a world where every man, woman, and child already owns an electric toothbrush. Not just any toothbrush, but the flagship model, packed with sonic pulses, Bluetooth syncing, AI-powered brushing advice, and more LEDs than a gaming PC. The toothbrush manufacturer, once raking in profits with each gleaming new unit sold, now stares into the abyss of market saturation.

So, how do they stay afloat? Enter the overpriced brush heads. Suddenly, the true business model reveals itself: not innovation, but maintenance. Not growth, but retention. Not toothbrushes, but subscriptions to the brushing lifestyle. It’s capitalism with a twist of dental hygiene.

This, dear reader, is the amusing yet alarming nature of saturation — a quiet force that seeps into economies, sciences, and even the very algorithms we build to make sense of the world. Let’s take a deep dive into what happens when the well is full, and we keep pouring.

Market Saturation: The Case of Diminishing Margins

Electric toothbrushes aside, market saturation has been the final boss of every product cycle. From color TVs to smartphones to SUVs with Wi-Fi and heated cupholders, markets grow fat and then weary. Initially, the excitement of a new product drives demand: early adopters queue, marketing teams rejoice, and stock prices soar. But as penetration nears 100%, the party quiets.

Consider:

- Smartphones: Once an annual ritual, upgrading your phone now feels like replacing a screwdriver — mildly satisfying, mostly utilitarian.

- Streaming Services: The 17th platform launching its own original series about gritty Scandinavian detectives starts to feel like cultural static.

- Home Assistants: Alexa, do people even want you anymore?

The economic effect is clear: Growth stalls, margins shrink, and companies pivot to selling accessories, subscriptions, or your data. Or, like Gillette before them, they try to reinvent the razor for a six-blade future.

Diminishing Returns and Infrastructure Saturation

Economists have long warned of diminishing marginal returns — the point at which adding one more worker or machine yields less output than the one before. In saturated contexts, this law comes home to roost:

- Agriculture: More fertilizer stops helping and starts hurting. Soil is saturated — biologically and chemically.

- Traffic: Add more roads, and the traffic flows — until everyone takes the new road and congestion returns with a vengeance. Known as the Braess paradox, it’s saturation with four wheels and a horn.

- Energy Grids: Renewables are great, but at some point, the grid’s capacity to absorb midday solar peaks becomes the limiting factor. Without batteries, we hit a saturation wall.

Saturation doesn’t scream; it simmers. It’s the moment you realize your third espresso shot just made your productivity worse.

Consumer Saturation: When Enough Is Too Much

Humans aren’t infinite wells of desire. At some point, we hit what economists euphemistically call “diminishing utility.” Your tenth subscription box of artisanal beef jerky doesn’t spark joy. Instead, it sparks an argument about pantry space.

Consumer saturation has psychological dimensions:

- Decision Fatigue: There are 42 kinds of toothpaste. Pick one.

- Aesthetic Fatigue: Instagram influencers now post photos of minimalism — because we’re saturated with over-curated maximalism.

- Cultural Repetition: Every film is a reboot, every song a remix, every ad a meme trying to sell you laundry detergent through emotional manipulation.

The modern consumer is drowning in choice and parched for meaning.

Research Saturation: Publish and Perish

Science, that noble pursuit of truth, is not immune to saturation. The academic publishing industry is producing more papers than any human (or AI) could reasonably read. This saturation manifests in several troubling ways:

- Redundancy: Ten papers on the same protein folding method. Slight tweaks, different authors, same conclusions.

- Citation Games: Papers citing each other in tight loops like academic blockchain — impressive, recursive, and possibly meaningless.

- Peer Review Overload: Reviewers are humans with inboxes. When every researcher is both submitting and reviewing, quality collapses.

Meanwhile, funding agencies suffer saturation in their own right:

- Risk Aversion: With too many proposals and limited budgets, agencies fund what’s safe, not what’s revolutionary.

- Buzzword Inflation: Every grant proposal contains the words “AI,” “climate,” or “resilience,” regardless of relevance.

Saturation in research leads to stagnation — the scholarly version of a traffic jam.

AI and the Limits of Learning: Saturation at Scale

Let’s now address the giant neural elephant in the room: Artificial Intelligence. AI models — particularly large language models (LLMs) — are voracious. Feed them Wikipedia, Reddit, every digitized book, and they’ll still ask: what else you got?

But what happens when they’ve read everything?

- Data Saturation: GPT-4 and its peers are trained on most of the Internet. Additional training data is either redundant, low-quality, or unavailable. The well is running dry.

- Model Saturation: Scaling laws — which once promised better performance with more parameters — show diminishing returns. A 10x model might only be marginally smarter.

- Inference Saturation: At some point, users don’t care about the nth decimal of accuracy. They want reliability, interpretability, and cost-efficiency.

- Task Saturation: LLMs are being shoehorned into every conceivable task. But not every task benefits from GPT-shaped tools. Some things — like cooking or genuine empathy — resist saturation by computation.

Moreover, AI-generated content is now saturating the same Internet it trains on. This recursive loop could eventually degrade future models. It’s like filtering seawater through a coffee filter — eventually, all you get is damp salt.

Saturation as a Catalyst

Saturation is not merely an end. It is also a crucible. When conventional growth chokes, transformation begins. Consider:

- Smartphone stagnation led to foldables, modular designs, and renewed interest in privacy-focused devices.

- Research saturation is giving rise to interdisciplinary hybrids — neuroeconomics, computational humanities, bio-inspired engineering.

- AI saturation fuels the need for neurosymbolic models, smaller context-aware agents, and the next generation of reasoning machines.

In other words, saturation is often a precondition for the new. It is the point at which old methods fail and new paradigms emerge — painfully, messily, but inevitably.

Conclusion: Living Beyond the Limit

We live in a world of abundance — of gadgets, knowledge, ideas, and algorithms. But abundance is not the same as growth. And growth, unchecked, hits limits. Saturation is the shadow of success, the ghost in the spreadsheet, the whisper that says: this is enough.

When toothbrushes become platforms, when every academic paper reads like the last, when your AI knows your email tone better than your spouse — it’s time to pause. Not to despair, but to observe. Because in that saturation lies a strange clarity: that the next great leap often starts with standing still.

And maybe — just maybe — brushing with an old-fashioned stick of wood isn’t regression. It’s rebellion.