In Isaac Asimov’s short story Light Verse, a woman hosts a party. She’s known for her hauntingly beautiful light sculptures—ethereal patterns that pulse and dance in the air like visual poetry. One of the guests, an engineer, notices that her robot butler is behaving oddly and, being helpful, decides to “fix” it.

Only after the repair does the hostess reveal:

“You’ve stopped the light sculpture. Max was the artist.”

Oops.

That scene has lived in my head for years. Not just because it’s one of Asimov’s cleverer jabs at our assumptions about intelligence and creativity, but because I, too, have had my “Max” moments—except I am both the robot and the hostess, and sometimes the well-meaning repairman is someone with an Instagram account and no sense of irony.

Let me explain.

I draw. With charcoal. With ink. With oil pastels, and on particularly brave days, watercolors. I’m not especially talented. I have poor stereoscopic vision, which means I can’t see depth like most people. (Stereoblind, they call it. I prefer “dimensionally humble.”) So I cheat. I print out images. I cut templates. I trace. I shade. I adapt. I make.

And then someone walks by and says, “But that’s not real art, is it? You traced that.”

And I smile with the warmth of a thousand erasers and say: “No, I conjured it from the void using wizardry and a Stanley knife.”

What these critics miss—what Asimov so brilliantly highlighted—is that creativity isn’t always located where we expect it to be. We want the artist to be dramatic, expressive, wholly original. But sometimes the artist is quiet. He traces. He stares. He redraws the same nose three times and still hates it. He uses tools, because tools are what separate art from cave walls.

In a world now flooded with AI-generated images—many unlabeled, often passed off as “real” human work—there’s something delightfully authentic about someone crouched over a lightbox muttering curses at masking tape. The AI never bleeds on the page. It never doubts itself. It never reworks the sky because “the emotion isn’t quite right.”

And that’s why I say:

It requires attention, intention, and persistence.

Not talent. Not divine inspiration. Just showing up and doing the work. Whether you’re a robot named Max, or a human with a scalpel and a low tolerance for nonsense.

So the next time someone tells you your traced drawing isn’t art, smile. Then hand them a brush and say, “Show me how it’s done.”

Forgery, Faith, and a Fine Brush: The Case of Han van Meegeren

In 1945, Dutch painter Han van Meegeren was arrested and accused of selling a priceless Vermeer to the Nazis—a crime tantamount to treason. Facing life imprisonment, van Meegeren made a startling confession: he hadn’t sold a Vermeer. He had painted one.

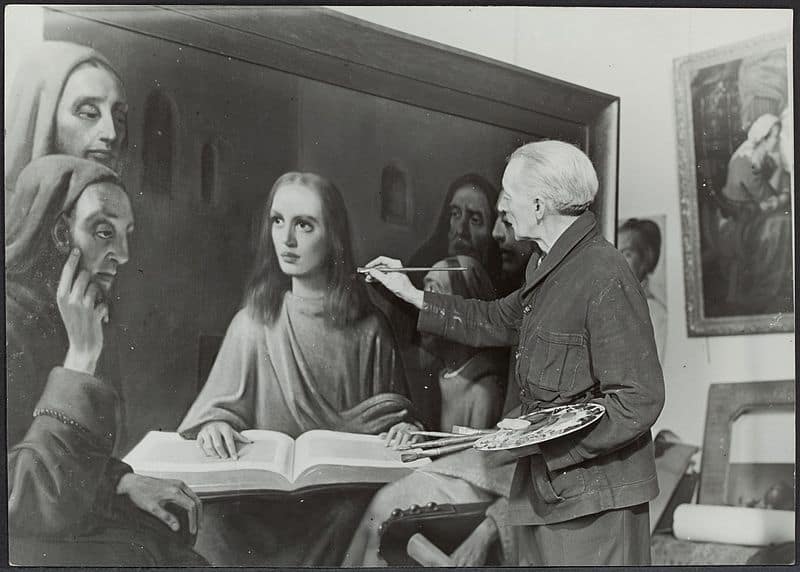

The work in question, Christ and the Disciples at Emmaus, had fooled the world’s top art experts. It was hailed as a lost masterpiece. And now the accused forger was claiming authorship.

Naturally, no one believed him.

So van Meegeren, under supervision, set up an easel and recreated a “Vermeer” from scratch—brushstroke by brushstroke, pigment by pigment. The photo above shows him at work, not just exonerating himself but reclaiming authorship of an image the world had once revered.

It’s the ultimate irony: only by proving he could fake it did he prove he was the real thing.

Like Max the robot in Light Verse, van Meegeren wasn’t what he appeared to be—but the art remained real, and the act of creation undeniable. His story reminds us how blurry the lines between originality, deception, and craft can be—and how often the tools and tricks of art are judged more harshly than the results.